Reducing CO2 within your organisation

.avif)

Defining congestion

Before we get properly into solutions, let’s take a look at how we characterise congestion. Traffic congestion is hard to define because it has both physical and relative aspects. In physical terms, it’s the way vehicles interact and hinder each other’s progress. As roads get busier, bad weather increases or an accident occurs, congestion is impacted. Equally, as demand for a particular road rises or there’s a diversion, traffic increases.

However, that definition ignores congestion meaning different things to different people. For instance, let’s say you live in the countryside. You may regard an unusually long queue along a winding lane as severe congestion. By contrast, a person living in a busy city may experience far longer daily hold-ups on a dual carriageway, and consider the same queue length as almost totally uncongested.

And so relatively speaking, congestion is also defined in terms of the difference between drivers’ expectations of the road network versus how it actually behaves.

Regardless, the impact of increased congestion is generally:

- Slower speed

- Longer journey time

- Greater queuing at junctions

- More stopping and starting

- Increased time spent stationary

- Unpredictable journeys

From an environmental standpoint, more congestion leads to greater pollution and CO2 emissions as vehicles spend more time at a standstill, braking and accelerating frequently, or travelling at very low speeds. These factors equate to lower engine efficiency.

What’s the problem?

Two words: greenhouse gases (GHGs). These trap heat in the atmosphere and include carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and fluorinated gases. When you buckle up in your car and start the engine, waste emissions release from the exhaust pipe.

Although a necessary byproduct, these emissions are harmful. How? They pollute the air, increasing the greenhouse gas effect. The greenhouse gas effect makes the Earth warmer, causing climate change.

Road transport: data and policies

Let’s take the UK and the US as case studies. The transport sector of these countries is responsible for emitting more greenhouse gases than any other, including electricity and farming.

- Worldwide, transport accounts for about a quarter of carbon dioxide emissions.

- Road traffic in the UK escalated from 297.6 billion vehicle miles were driven on Great Britain’s roads in 2021, an increase of 11.9% compared to 2020.(GOV).

- Emissions from road transport have declined less than anticipated over the last twenty years (European Environment Agency).

- The Department for Transport estimates a petrol car journey from London to Glasgow emits about four times more carbon dioxide per passenger than the equivalent journey by coach.

Plans and policies are in place to tackle climate change and emissions. For example, the primary aim of the Paris Agreement is to keep global temperature rises well below 2 degrees Celsius (preferably 1.5), compared to pre-industrial levels.

Moreover, the EU is striving to be climate-neutral by 2050. What does that mean? An economy with net-zero GHG emissions. That objective is at the heart of the European Green Deal.

Additionally, the UK’s transport decarbonisation plan laid out in July 2021 outlines commitments and actions required by the government, including the pathway to net-zero transport by 2050. If these 2050 goals are to be reached, lowering road transport emissions must form a major part of strategies.

A key takeaway? Daily commutes impact the carbon footprint of an organisation.

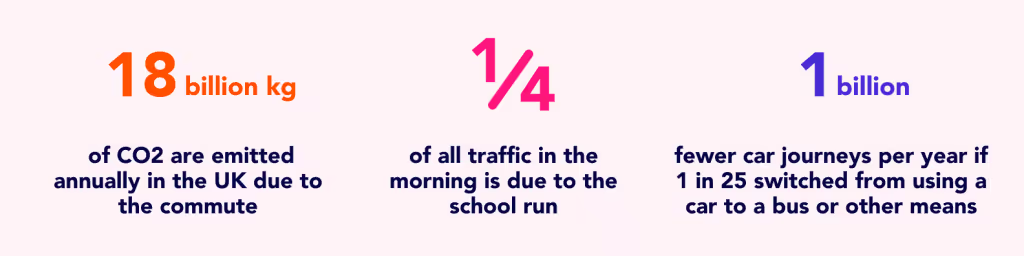

Sustainable commuting and school transport

Organisations play a large role in encouraging sustainable travel and implementing alternative and affordable commuting solutions.

For example, a staff transport service has sustainability at its heart. Smart, safe and customisable, this transport service for commuting and school runs is streamlined, customer-focused, and easy to use.

Making the most of top-notch technology, Zeelo users benefit from:

- Mobile apps to buy and manage subscriptions

- A central platform to manage and allocate trips

- 24/7 support from friendly and knowledgeable staff

- Enhanced DBS checked drivers

- Live vehicle tracking and service notifications

And in terms of sustainability, businesses and schools are able to reach environmental goals. How? Zeelo’s transport service removes about 30 cars from a car park and the road, reducing emissions. Fewer cars and the resulting CO2 reductions help organisations reach emission targets.

Moreover, every 22 kilograms of carbon dioxide saved is the equivalent of one tree planted. By offering an alternative commuting service to 100 people, that saves 403 kilograms of carbon dioxide each day – the equivalent of 91 tons a year or planting 600 trees.

Since then, Zeelo also offers net-zero commuting, giving customers the opportunity to use a fully managed electric bus service.

Carpooling, walking and cycling

Vehicle sharing is low-cost, efficient and easy, leading to the number of cars on the road decreasing and emissions falling. And for employees, parents and children living close enough to work or school, walking should be encouraged. Not only is there a positive environmental impact, but also a benefit to people’s health and wellbeing.

Another alternative? Organisations should encourage hopping on two wheels by incentivising cycling.

Electric vehicles

In the UK, new petrol and diesel vehicles will be banned from sale in 2030. As a result, electric and plug-in cars will become more mainstream and should be encouraged by organisations in the meantime.

In 2016, 11 businesses including Microsoft UK, University of Birmingham and London Fire Brigade were awarded ‘Go Ultra Low Company’. They led the electric vehicle revolution by using electric vehicles for day-to-day activities.

And in 2020, electric vehicle purchases in the UK by businesses and fleets almost doubled those bought by private buyers.

Additional ways to reduce CO2 emissions

For a start, be sure to measure and track the carbon footprint of your organisation. That way, it’s easier to put GHG reduction strategies in place. To help provide a uniform approach to reporting, three distinct ‘scopes’ are defined by the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard, helping organisations prepare true and fair emissions inventory.

Alongside that, what else can organisations do to lower carbon dioxide emissions?

- Go green with energy suppliers

- Office changes such as using energy-efficient lighting

- Reduce business aviation travel

- Invest in a Revolving Green Fund

- Consider Climate Partner

- Retain a degree of remote working

- Recycle and reduce waste

Tackling harmful emissions

The transport sector is a large emitter of greenhouse gases. GHGs from energy supply has reduced by 60% since 1990; from transport, emissions have fallen by a mere 2%. To meet policy targets and help reduce CO2 emissions, organisations have tons of sustainability options, from diverting to green energy to implementing simple changes to the office environment.

From a transport perspective, Zeelo is a prime example of a sustainable commuting and school transport solution. By reducing congestion and therefore lowering emissions, their fully managed bus services help organisations reach environmental goals. To find out more get in touch with Zeelo.

We help companies and schools achieve their transportation program goals

Corporate shuttles

Warehouse/Distribution

Schools & Universities

Become a partner

Want to know how we can help you?

.avif)

.avif)